- By Rhode Island Monthly

- In News

- Posted Sep 13, 2011

Life on the Line

When Nick Rabar left a cushy job at the Chow Fun Food Group to open the restaurant of his dreams, it nearly became his ultimate kitchen nightmare.

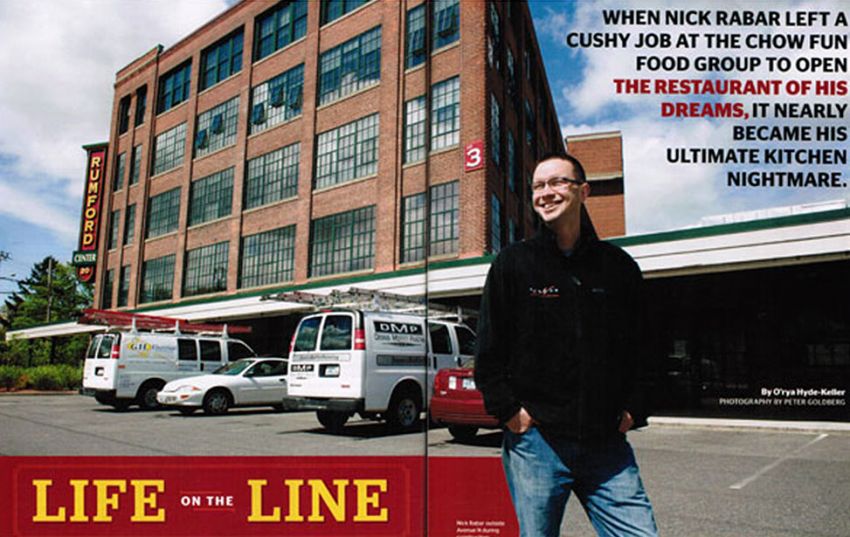

One thousand one hundred and twenty-one. One thousand one hundred and twenty-two. One thousand one hundred and twenty-three. It’s an early fall night in 2010, and Nick Rabar stands on the corner outside Rumford Center during rush hour. He is counting cars. Over the course of two hours, nearly fifteen hundred vehicles whiz by. To Nick, these commuters speeding home after work aren’t traffic. They are potential diners. And a lot of them. And even though he is on the verge of closing a sweet deal that would make him the owner of an 1,800-square-foot restaurant in downtown Attleboro, a restaurant where he would have the money and control to do pretty much whatever he wants, even though he is, at the same time, on the verge of personal financial disaster, Nick realizes while counting those cars that he doesn’t want to open a restaurant in Attleboro. He wants to open one in the town where he lives? - right here in Rumford.

This was actually the original plan. But as things go when you’re trying to open a restaurant, the plan doesn’t always play out. Sometimes the plan brings you to places you’d never imagined. A year earlier, Nick had been John Elkhay’s protégé, helping the well-known Rhode Island restaurateur open and run restaurants such as Citron, Luxe Burger and Chinese Laundry.

As a vice president and the corporate executive chef at Elkhay’s Chow Fun Food Group, Nick had considerable creative and managerial control. And the Elkhay apprentice had gotten a lot of attention during the decade he’d worked there: Spirit Magazine proclaimed him one of the nation’s brightest young chefs; the Rhode Island Hospitality Association pronounced him chef of the year in 2003; the restaurants he ran received accolades from critics; and he had his own cable TV show. But by 2009, Rabar was ready to fly the nest, and he started to dream of opening his own restaurant. Young, ambitious, talented and a veteran of multiple restaurant openings, Nick knew it wouldn’t be easy, but he didn’t know how hard it would be.

When Nick left the Elkhay empire in December 2009 – parting amicably, they both say – he left with a big idea, actually an Elkhay-ish idea: a 3,400-square-foot, 120-seat restaurant in the newly remodeled Rumford Center complex, an industrial building rehabbed into a mixed-use development. Streetlamps would line the walls, and giant clusters of pendant lights would hang from the ceiling over lush leather banquettes. There would be a chef’s table with its own kitchen where diners could watch their personal chef prepare dinner, and glass-walled private booths so guests could peer through into the kitchen. The location was a bit out of the way, but Rumfordites didn’t really have a local eatery, and successful restaurants were popping up in suburbs all over the state (think Persimmon in Bristol and Billy’s in Barrington). East Siders and people from downtown Providence would surely wander over the Henderson Bridge. And if 617 area codes started showing up on the reservation list, then all the better. He also had investors who were psyched about his idea and ready to finance his vision. A month after he left, a story in the Providence Journal declared July 2010 the anticipated opening date – much to the surprise of the principals at the company that owns Rumford Center; they thought they were just starting to negotiate a deal.

But by July, Nick had lost his investors. He was out of work and in debt from the initial design stage. He had recently gone through a divorce and a short sale of his house, so his personal credit was demolished. And he and his new wife, Tracy, had two kids at home and a baby on the way. This was not how he had added it all up in his head. And so, Nick started to add up cars.

Any restaurateur will tell you: The restaurant business is a risky and punishing one. Even if you graduate with a prestigious culinary degree, you still have to pay your dues – or, rather, get paid minimum wage to work at the bottom of the ladder as a dishwasher or prep cook. Hours are long, margins are low; the work is grueling. Drug use, alcoholism, depression – all symptoms of an adrenaline-driven culture where you make the party food when everyone else is partying. If you’ve managed, like Nick, to be in the restaurant business and have a family, it’s tough to find time to spend with them. "When you’ve been working eighty hours a week, mostly at night, and you wake up and your kid wants to play with you, it’s hard when the only thin you can really do is crawl to the coffee maker," says John Elkhay, Nick’s old boss.

And if you open up your own restaurant, thinking this will give your life some flexibility and control, good luck. One study shows that 27.5 percent of independent restaurants fail in their first year, and 61 percent fail by their third. Because of those bleak numbers, banks generally consider restaurants much riskier ventures than other small businesses, so it can be nearly impossible to get start-up funding, especially during a recession.

And chefs often have a difficult time transitioning from the back of the house – coming up with creative menu ideas and slinging sauté pans – to the front, where they must do everything from glad-handing and public relations to tallying the tax bill and fixing the air conditioner. And then there’s the competition – not only the crowds of independent restaurants vying for diners, but also the chains, where efficiency and uniformity mean patrons get exactly what they expect night after night. Talk at length to any restaurateur and inevitably they will compare putting their food on your table to a battle. "In the restaurant business, you’re basically in a minefield," says Elkhay. "And there are bombs going off all the time."

So why do it? Why enter a risky business that may very well offer little or no reward? Especially when, like Nick, you have to leave a cushy job to do it. "A restaurant is a place where you can be passionate in a world that is largely taking passion out of the equation," says Bob Burke, who has owned providence’s Pot au Feu for more than twenty-five years. It’s a business, he says, that attracts artists and gypsies, as well as extreme extroverts, charismatic crowd pleasers and adrenaline junkies – personality types who would never feel comfortable working nine to five in a cubicle, people who crave constant action and who want to see, immediately, the products of their labor. "In this business, we take raw materials to finished goods in eighteen hours," he says. "It’s real, it’s present, it’s engaging, it’s exciting, it’s instant gratification. And that’s what people who come to the restaurant business crave more than anything else. That’s their heroin. That’s what they’re addicted to."

Nick is definitely the type. He’s all energy, the kind of person you wish you could plug yourself into the morning after a sleepless night. He’s also a talker, an articulate and compelling one – the guy could sell McDonald’s to Michael Pollan (not that he would). And even though his passion for the restaurant business can at times seems a bit exaggerated, maybe even a bit forced, he’s ultimately a guy you want to root for, especially when he talks about the last two years.

During his career, Nick managed to escape many of the pitfalls of being in the restaurant industry – until he decided to open his own. His time at the Chow Fun Food Group was marked by a quick ascension up the corporate ladder, starting at Ten Prime where he worked as the kitchen manager and culminating in his vice president position. In a business that can attract some dark characters, Nick was friendly, positive, dependable and well-liked. But to open a restaurant, that’s just not enough.

"He had great relationships in the industry, plus he’s a nice, nice person, he works really hard, and he’s good at what he does," says Colin Kane, one of the principals at PK Rumford, the LLC that owns Rumford Center. "And I think he thought that all these relationships would translate into an operating restaurant within a couple of months. But practically speaking, even with all those relationships, you still need capital. And Nick had a particular challenge. He was starting from scratch. It wasn’t even a built-out restaurant with a kitchen. It was a box of air in a allocation that’s not proven."

So when he and his funding partners couldn’t agree on terms and unexpectedly split in March of 2010, Nick was left with no plan and a stack of debts. He went to more than twenty financial institutions begging for money, but no one wanted to give a loan to an untested, first-time restaurant owner – even a well-connected one. "When my funding partners left, all momentum came crumbling down," he says. "It was a very hard time. You would be astonished how, when you’re not the downtown big shot wearing a suit during the day and your chef coat for p.m. service, how fast your phone stops ringing and how fast people can forget about you. If it weren’t for Tracy and the kids, it would have been an all-time low." Before, it seemed as if the opportunities were endless; now, Nick wondered if he’d be able to pay his bills. He began looking elsewhere, even interviewing for jobs at other restaurants, the ultimate sign of defeat. Times were tough, and he had mouths to feed. But the box of air kept pulling him back. Sometimes at night, after the kids were asleep, he would driver over and just stare at it.

Then and opportunity arose. The city of Attleboro, looking to attract business and people downtown, offered Nick a business grant plus a ten-year, three-percent loan to start a bistro there. It would have always been a good deal, but during the great recession, it was a fantastic deal. Nick and Tracy started to outline the details. But Nick’s hear wasn’t in it. He just couldn’t shake Rumford, kept trying to work it out in his head. That’s when he started counting cars.

The winter after he’d lost his backers, he and Tracy headed to Chardonnay’s in Seekonk. As they sat at their table, they mulled the paperwork they had in had, the papers that would seal the Attleboro deal. "If we sign this, we lose Rumford," Nick said to Tracy. As if on cue, in walked Colin Kane. To Nick, it was a sign. Fate. Over the last year, Nick had been humbled, sure. And, okay, maybe he simply couldn’t afford an over-to-top, 120-seat restaurant. But his restaurant belonged in Rumford Center. He was sure of it. And this was his last shot. He walked over to Colin and asked it they could revisit it again, maybe think of a creative way to pull it off. Colin said, "I’m in."

The next day, Tracy and Nick walked through the space in Rumford Center next to Seven Stars with the rest of the PK group, his design team and his contractor. Everyone wanted Nick in there, and together they figured if he could slash the size of the restaurant – more than halving the space, reducing seating capacity from 120 to forty-six, shrinking the scope and ambition of the menu and the depth of the wine list – they could make it work. The new concept: a small, sophisticated neighborhood gathering place where locals could go for reasonably priced, locally sourced food. And in January 2011, after hammering out the details – including funds creatively cobbled together from PK Rumford, a loan from the city of East Providence, Nick’s parents, and the little bit of savings he and Tracy had left – after two years of waiting and hoping and praying and struggling, construction on Nick’s box of air, Avenue N, finally began. As if to signify that this was truly a time of new beginnings, Tracy and Nick’s son Wynn was born three days later.

It’s April 2011, a month before what Nick hopes will be opening day. Nick sits at a table in Seven Stars, the bakery and coffee shop that has served as an ad hoc office these last six months. It’s a typical Nick move – sincere (there’s no space for a desk in his tiny restaurant), but also somewhat calculating. Not only does hanging out at Seven Stars make him seem like just another Rumford Joe in keeping with the hyperlocal theme of his restaurant (he calls Avenue N a "mom and pop restaurant" even though it’s anything but), it also gives him essential face time with the community. It seems like nearly every citizen of Rumford comes through here at one point or another. And Nick knows most of them. (he confesses that he “love to canoodle.â€) The fate of his restaurant may rest not so much in his food as in his amazing ability to be simultaneously authentic and politically savvy.

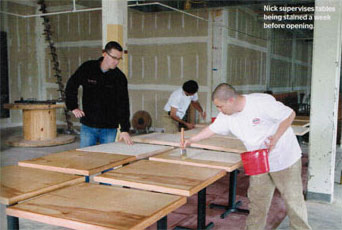

Nick has spent the previous day interviewing potential staffers with Tracy, who also worked for Elkhay and will now run the front of the house. They couldn’t get a babysitter, so they quizzed potential sous chefs about their experience and cooking philosophy while taking turns walking ten-week-old Wynn back and forth to keep him calm. Construction is progressing relatively smoothly. Well, except for one hitch. Nick’s original plan didn’t include a hood, which meant no deep frying, no grilling, no smoke. And the more Nick imagined his menu, even the pared-down version, the more he knew he needed a kitchen that could do more. The cost of the hood and venting system was steep: 60,000 unanticipated dollars. But the problem now is it’s a new model that the subcontractor has never installed, so the crew is running behind. This puts the whole restaurant on hold because the kitchen can’t go in until the hood does. Right now, Nick’s kitchen is a puzzle that’s missing a crucial piece.

Nick wants to open Mother’s Day weekend, but because of the venting issues, it may not happen. He is many days behind. And he knows everything must be absolutely perfect before he can reveal his creation to the public. "You have to open strong from plate one at all costs," he says. "Because after plate one, you’ve set the standard for who you are. No matter what, you have to fight your ass off to make it perfect. If we don’t do it from plate one, then we’re out of time."

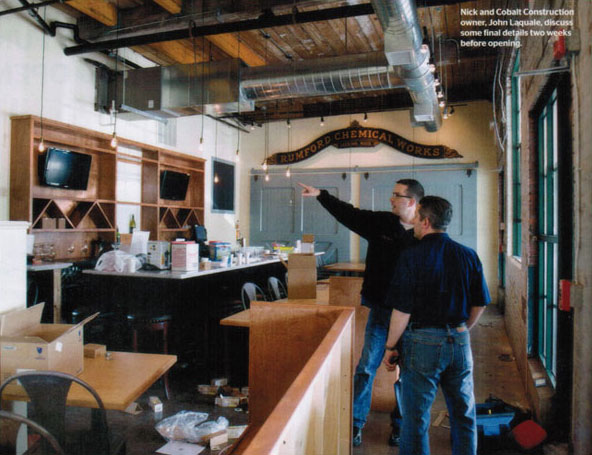

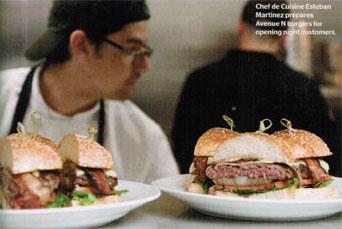

They miss Mother’s Day weekend, but Avenue N opens only a few days later, and the crowds do show up. They stand at the bar or sit on galvanized metal chairs under open beams and ductwork. A large Rumford Chemical Works sign adorns the far wall, a nod to the building’s past. The tiny restaurant’s layout revolves around the white, marble-topped bar, and though there are no glass walls, you can still peek into the kitchen where Nick and his crew prepare a menu that’s best summed up as upscale pub food – with dishes that range from Reuben sliders and corn dogs to Block Island black bass served over new potatoes and crispy oysters. It’s much less Elkhay than the original plan and way more Nick: still not subtle, but intimate and friendly.

The night goes off without a hitch. Almost. The liquor license caused some scrambling and posted only a few hours before opening. And there are some minor computer glitches. (It’s charging people for soda refills, and staff can’t figure out how to input salmon without the sauce.) But the kitchen flow, which could have been a dogfight with cooks running in all directions, seems to be working, something Nick couldn’t have known for sure until his restaurant was filled with diners.

A few weeks later, the restaurant is packed at nine o’clock. Judging by the crowds, Avenue N has obviously filled a need in Rumford. And curious foodies from throughout the state and Massachusetts are definitely checking the place out. Nick, normally a study in motion, actually pauses for a moment to take it all in – the clinking glasses, the smiling faces of his guests, plates coming back empty. One of his serving staff teases him, "Are you, like, basking in your creation?" And Nick realizes, yes, that is exactly what he is doing, elated by this accomplishment that has been so long in the making. "When you actually see it through your eyes, not just when you close your eyes and imagine it, it gives you chills," he says. " prayed and hoped that his restaurant would be exactly what it is."

But this is his fiftieth day without a day off (the restaurant is open seven days a week). And there have been some hiccups, including several unflattering Yelp reviews and undercover sting that found an Avenue N waiter serving a minor planted by police. Thought he insists he’s having the time of his life, you have to wonder if all this will start to take a toll.

Chefs use the term mise en place, literally "putting in place," to describe the precise preparation and positioning of equipment and food before service begins. It’s what enables them to turn out dozens of beautifully prepared meals in the time it would take a layperson to cook just one. But for the chef-owner, mise en place is more than just order in the kitchen, it’s that consummate moment before your first guest arrives, when everything is just right – from the composition of your menu and volume of the music to the texture of the tablecloths and the size of the wine glasses. For a restaurant to thrive, all of these details must be in place. And the difference between a good restaurateur and a great one isn’t just getting it perfect, it’s getting it perfect without the customers ever noticing. But maintaining that flawless moment night after night requires an almost superhuman stamina. Ultimately, a restaurant is an illusion supported by sweat, and that’s why so many fail in the long-term. As Elkhay says, "The restaurant business is a young man’s game," and working non-stop won’t keep you young for long. So far, the cars Nick counted have indeed been stopping at Avenue N, but will they continue to stop? And if they don’t, at what cost?

“It all gets real really fast,†says Burke about going from working in a restaurant to opening one. “It’s the difference between playing poker with your friends with plastic chips and playing a high stakes table with next month’s mortgage money. All of a sudden, you know how real that is. And there’s going to be a moment in Nick’s process when it dawns on him – this is for keeps.â€

For the most part, Nick’s almost uncanny confidence seems unshakeable. But occasionally, you get a sense that the last two years have been more than just a struggle, more than just a bump in the road, that Nick has, in fact, already had the moment when he realized this was for keeps. And it has shaken him to the core. He knows what it’s like to be right on the brink of failure with everything on the line. And while he’s the sort that thrives on risk, the exact personality that is drawn to this exciting, fast-paced, ephemeral business, he knows now that it takes more than one battle to win a campaign.

“It’s like a war. It’s a war every night. Not against your own clientele, but against your own setup – against your own mental mise en place and against your own physical mise en place,†says Nick. “It’s like, if you’ve set it all up just right…then you’ve survived, but you know what? Tomorrow night you’ve got to do it all over again. It’s a business that’s always going. There’s never an end.†He pauses. “Well, you hope there’s never an end.â€

- By O'rya Hyde-Keller at RI Monthly, Photos by Peter Goldberg -

Gift Cards

Latest Posts

The Pantry at Avenue N - Best Pantry

- Jul 21, 2015

- In Accolades

SPRING FLORA • THE BALMBAY

- Apr 11, 2015

- In Recipes

R.I. Chef of the Year shares a simple but elegant holiday...

- Dec 17, 2014

- In Recipes